Georgian Witnesses

12 / GEORGIAN CAMPAIGN STRATEGIES TO END THE TRADE IN CAPTIVE AFRICANS AND, LATER, TO ABOLISH SLAVERY

CONTEXT

The case for the slave traders and the slave-owners in the Caribbean plantations was chiefly upheld by law, custom and inertia, and was also strengthened by vigorous behind-the-scenes lobbying by the ‘sugar interest’.

[On this subject, see M. Taylor, The Interest: How the British Establishment Resisted the Abolition of Slavery (2020)].

Opposition, however, was strengthened by imaginative tactics on the part of the Abolitionists.

12.1 GRAPHIC IMAGERY OF THE TRADE:

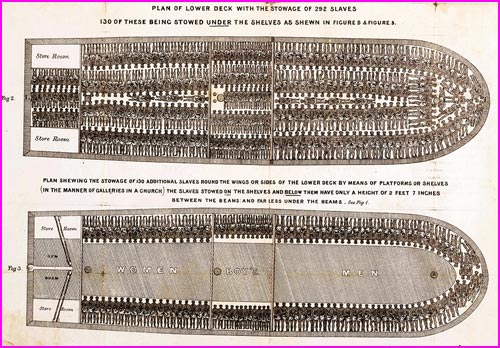

Diagram of The Brookes (1787), showing a slave ship, trading out of Liverpool, which regularly made the trans-Atlantic crossing from Africa to the West Indies laden with human cargo, chained and inhumanly packed. The diagram showing 422 captive Africans, stowed on the lower deck and on additional platforms, made ‘an instantaneous impression of horror upon all who saw it’, as recorded by leading abolitionist, Thomas Clarkson.

The image was widely circulated, being printed in newspapers and books, as well as posted on walls of coffee-houses and taverns. Given that the sea-crossing took between six to eleven weeks, depending on wind and weather, and that the captives lay in squalor for all but one hour a day, when they were taken on deck for fresh air, it is unsurprising that rates of illness and death were high. (It is estimated that 15 – 16% of captives died during the journey, though, for ships using the ‘tight pack’ system, that figure may be too low). In 1788, the British Parliament legislated to control the number of captives that each British-owned slave-ship was permitted to carry, according to its weight. In addition, a doctor was supposed to accompany each crossing, keeping records on the state of the captives and receiving a bonus for the number surviving the journey. (The Act had to be renewed annually, until made permanent in 1799). However, enforcing such legislation proved difficult – a classic problem still facing anti-slavery campaigners.

12.2 ABOLITIONIST MEDALLION & CAMPAIGN IMAGE

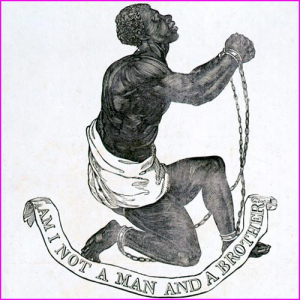

Abolitionist Medallion (1787): it was widely circulated by the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade and the design was reproduced in cameo brooches for ladies, as well as in paintings and on metal tokens, in all formats incorporating the humanist appeal: Am I not a Man and a Brother?

To some twenty-first-century sensibilities, the kneeling posture of the African supplicant can seem too supine. It does not record the contributions of the enslaved populations to their own cultural survival and eventual liberation. However, the image was devised not to threaten or to alarm but instead to jolt the consciences of people living far away from the actual experience of slavery – but who benefitted from goods produced by an enslaved workforce. It made a powerful appeal to a basic and universal humanism, in opposition to those who argued for an innate hierarchy of peoples, with some ‘inferior’ races being ‘natural’ slaves.

12.3 LOGO OF HUMAN SOLIDARITY

‘May Slavery & Oppression Cease throughout the World’: plain words used in one design for the observe of the Abolitionist Medallion (1787), as shown here. This message was unequivocal. It opposed not only slavery but all forms of oppression. And it aspired to world-wide liberation.

The handshake is an egalitarian style of greeting, which was gaining currency in eighteenth-century Britain; and which affirmed a universalist humanism. In reality, the extent of handshaking between people of different classes and different ethnic groups, identified as separate ‘races’, was limited on a day-to-day basis. However, this powerful image of friendship was visually clear and unambiguous, as was the message in words.

12.4 PARLIAMENTARY ORATORY

William Wilberforce’s first speech in Parliament (12 May 1789) in favour of the abolition of the slave trade. Beginning modestly, Wilberforce spoke for three hours with great power. He commented upon the state of the slaves in transit, with the simple words:

‘So much misery condensed in so little room, is more than the human imagination had ever

before conceived’.

He made it clear that he was broadening the debate from an attack on the Bristol and Liverpool traders into a national confession, hence demanding national redress:

‘I mean not to accuse any one, but to take the shame upon myself, in common, indeed, with the whole parliament of Great Britain,for having suffered this horrid trade to be carried on under their authority. We are all guilty – we ought all to plead guilty, and not to exculpate ourselves by throwing the blame on others; and I therefore deprecate every kind of reflection against the various descriptions of people, who are more immediately involved in this wretched business’. And Wilberforce ended with a quiet emphasis: ‘Having heard all of this, you may choose to look the other way but you can never again say that you did not know’.

Wilberforce’s bill was rejected in the House of Commons; but his speech was circulated widely in a printed version, greatly aiding the abolitionist cause. And in 1807 a brief-lived coalition government, known as the Ministry of All the Talents, which included opposition Whigs like Charles James Fox, legislated to outlaw Britain’s role in the slave trade.

[There are differing transcripts of this seminal speech, varying with the art of the listening scribe; but Wilberforce’s general case – and his rhetorical power – remain the same in all variants: see B. Carey, British Abolitionism and the Rhetoric of Sensibility: Writing, Sentiment, and Slavery, 1760 – 1807 (Basingstoke, 2005).]

12.5 AFRICAN TESTIMONY

The Sons of Africa constituted a campaigning group of free Africans, many being formerly enslaved, which flourished in later eighteenth-century London. It had at least 15 members (numbers varied), who wrote and lobbied against slavery, working closely with the English abolitionists.

The best known was Olaudah Equiano (1745 – 97), who published initially under the non-de-plume of Gustavus Vasa, and who toured extensively, lecturing on the evils of slavery. Thus in 1791 he spent some months in Ireland; and in 1792 he lectured in Scotland, as well as at public meetings in Cambridge, Durham, Manchester, Nottingham, and Sheffield.

Above all, it was his publication of a personal memoir, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vasa (1789) that attracted attention, going into nine editions during his lifetime. His African testimony, written with eloquence, had great impact, as it combined authenticity and dignity, with a clear moral message. Equiano’s most famous rhetorical question thus asked simply:

‘But is not the slave trade entirely a war with the heart of man?

Implicitly, too, the presence in Britain of Africans like Equiano and numerous others, rebuked crude racist stereotypes – so that, while an unknown but sizeable number of Britons in this period did hold Africans and West Indians in low esteem, there was a rival tradition of anti-racism, which stressed a universalist humanism. Such rival responses provide a reminder that Britain was a society divided on the question of slavery and anti-slavery – neither completely racist nor wholly anti-racist but a society of rival (and fluctuating) views.

[See B. Carey (ed.), The Interesting Narrative/ Olaudah Equiano (Oxford, 2018)]

12.6 THEATRE

In the course of the eighteenth-century, representations of Africans on the British stage became more variegated. Some dramatists continued to pillory them as figures of fun; but others allowed them a shared humanity. In the early nineteenth century, too, Ira Aldridge (1807 – 67), an American-born black actor, made his name in a series of Shakespearean roles, even while facing considerable racist hostility. Rather than offering one single view, theatre provided a forum where diverse attitudes could be articulated in dramatic form – with a degree of ambiguity and interpretative scope.

Three significant plays from the 1780s all included noble African/ Caribbean characters but with different ideological implications:

12.7 Inkle and Yarico: A Comic Opera (1787) by George Colman the Younger, was loosely based upon a story by Richard Steele (1711) and may have been further triggered by sight of an unpublished play sent in 1787 by the radical John Thelwall to George Colman Senior.

[For more on John Thelwall (1764 – 1834), see Witnessses 15-6].

The plot featured a cross-ethnic love affair, between Thomas Inkle, a white trader who is shipwrecked in the West Indies, and Yarico, an Indian woman, which is complicated when Incle contemplates selling Yarico into slavery for financial gain. The charged story, pitting love against financial incentives and social prejudices, had an instant success on stage, with productions in Dublin (1787), Jamaica (1788), New York (1789), Philadelphia (1790), Calcutta (1791), Boston (1794), and Charleston (1794).

12.8 The Prince of Angola: A Tragedy (1788), adapted by J. Ferriar from Southern’s Oroonoko: A Tragedy (1696), itself adapted from Aphra Behn’s novel Oroonoko: The Royal Slave (1688). The story is tragic, featuring a noble African prince, Oroonoko, who faces enslavement and the loss of his great love, Imoinda. Having organised a failed rebellion, he then kills his love and himself. In the eighteenth century, the story was best known in its dramatised form by Southern, with Imoinda changed into a white heroine, in love with her African prince, yet simultaneously pursued by a white governor, creating an emotionally charged love triangle. Southern’s romantic tragedy was not explicitly presented as anti-slavery; but it was increasingly interpreted as such, as it featured sympathetic African characters of dignity

and humanity.

The play’s further adaptation in 1788 by John Ferriar (1761 – 1815), a Manchester physician who supported abolition, altered the text to make its message explicitly

anti-slavery.

12.9 By contrast, The Benevolent Planters by Thomas Bellamy (1789), offered an alternative view, which, as its title suggested, opposed abolition. The plot featured two young lovers, born in Africa, who were transported to the West Indies as slaves. There they were separated but eventually reunited, to live respectable and productive lives, under the benevolent care of the plantation owners, who are represented as having the slaves’ best interests at heart.

Clearly, the play’s overall message was conservative, but it did imply that the mutual love of the two Africans was humanly admirable and socially to be encouraged. No comic African figures here; and no harsh plantation owners, dividing families and lovers. The story was a fantasia, far from social realism – offering a supposedly happy ending to the anguish of transportation and separation. The aim of these productions was to entertain audiences while carrying different ideological messages; but, subliminally, the stories also encouraged a sense of shared humanity and common human emotions, among peoples with different backgrounds, customs and skin colours.

12.10 PETITIONING

Another significant tactic was the use of petitions, to show Parliament that the movement for abolition had public support that stretched well beyond the efforts of the few leading abolitionists. Thus in 1792 when Wilberforce returned to the attack, the huge total of 519 petitions were presented to Parliament.

Most of the 390,000+ signators were men but some women’s names were included among them. In 1792, the Commons were persuaded to vote for the gradual abolition of the slave trade but the bill was lost to delaying tactics in the House of Lords. Another wave of petitions in support of Abolition was sent to Parliament in 1806 – 7, to counteract petitions against the change from slave traders, sugar refiners and plantation owners.

Before the 1833 legislation instituted by the new Whig government to abolish slavery in Britain and its colonies (except India), many more petitions were presented to Parliament. A few came from those with vested interests in the status quo. But a huge number came from rank-and-file protestors, organised by the Anti-Slavery Society. Over 5,000 petitions were presented in favour of Abolition, signed by one and a half million Britons; and the national female petition in 1833 recorded 187,157 signatures, being the largest single antislavery petition presented to Parliament.

Petitioning was by no means a new tactic for extra-parliamentary campaigners; but it was used with ever-greater zest and urgency in this period, allowing private individuals to express their views. In a number of cases, local petitions followed big public meetings which served to influence local opinion; or they were encouraged by the churches, especially the Quakers. For MPs, in the absence of opinion polls, petitions offered some guide, however imperfect, to the state of the wider public opinion.

12.11 ORGANISATION – THE SUGAR BOYCOTT

Between 1791 – 3, the Anti-Saccharine Society, with British contact points in Birmingham, Bristol, Edinburgh, Liverpool, London, Manchester, Newcastle, and Oxford, as well as overseas in New York, Paris, Philadelphia and Sierra Leone, organised the world’s first systematic consumer boycott. The target was West Indian sugar and rum, coming from plantations worked by an enslaved labour force. It may be that as many as half a million people in Britain joined the boycott, indicating the potential power of organised consumers. Despite causing an initial dent in sugar consumption, the first sugar boycott petered out from 1793 onwards, as political attention turned to reactions to the French Revolution and the ensuing long war with revolutionary France. In the 1820s, however, the campaign was revived by Elizabeth Heyrick (1769 – 1831), a Quaker from Leicester, who was dismayed at the slow progress of the Abolition movement.

‘If people must have the “sweet dust”’, she declared, they should at least ensure that it was grown in Britain’s colonies in the East Indies – such as Bengal and Malaya – where canefield labourers were impoverished but at least technically free. In her pamphlets, she further urged: ‘Let the produce of slave labour henceforth and for ever be regarded as “the accursed thing” and refused admission to our houses.’ Heyrick’s populist campaigning and calls for a moral revolution were regarded with some suspicion by respectable parliamentarians, of whom in turn she was often critical. But their collective efforts helped to accumulate support for Abolition.

Consumer boycotts can have considerable force but, for best success, they require overwhelming public support, which is not always easy to obtain and then sustain.

12.12 ORGANISATION – NETWORKS OF LOCAL SOCIETIES

Organisation added strength to the campaign by recruiting local support, circulating abolitionist literature, and encouraging long-term commitment, even at times of short-term failures.

[For context, see M.J.D. Roberts, Making English Morals: Voluntary Association and Moral Reform in England, 1787 – 1886 (Cambridge, 2004).]

Some Quakers, with their egalitarian ideas and practices, first expressed their outright hostility to slavery in Pennsylvania in 1688; and there was continuing unease in Quaker circles in Britain, before in 1761 their Yearly Meeting (convention of Societies) expressed its strong opposition to slave-trading.

In 1787 a formal Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was established, with strong support from Nonconformist groups, especially the Quakers, plus various freed former slaves, living in England, and key activists who were liberal philanthropists, like Wilberforce. The Committee established a network of local societies, making them not only a political lobby group at Westminster but also a cultural and educational force across the country. One individual response to the abolitionist case was recorded in 1806 by the painter John Hassall (c.1767 – 1825), who was not an activist but a man with a

liberal conscience:

‘In the name of honour, justice and every virtuous feeling, let this impious traffic in human blood be at once abolished, nor let it be imputed to Great Britain that she has conducted trade at the sword’s point – staining the white robe of commercial justice red. May the just efforts of those philanthropists be finally crowned with success, who have hitherto fostered the hopes of restoring to the distressed and tortured negro his long lost family, for no other crime than being guilty of having a skin differently coloured than our own’.

[Seer J. Hassell, Memoir of the Life of [George] Morland (1806), p. 144].

In 1823, a group of campaigners adopted a more ambitious project, forming the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Dominions, which quickly became known as the Anti-Slavery Society. Hundreds of local societies were founded, with substantial participation from women, who were otherwise excluded from direct political participation. Local groups included The Birmingham & West Bromwich Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves (1825), one of its founder members being Eliza Heyrick (see above 12.8). The Society was united in its major aim but faced divisions between those, like Heyrick, calling for immediate abolition and those favouring a more gradualist approach. This Society was dissolved when its prime aim was achieved with legislation relating to Britain and its colonies in 1833.

In 1839, however, the Quaker Joseph Sturge founded a successor body, named the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, to end slavery world-wide. With various mergers and changes over time, this organisation continues, known today as Anti-Slavery International:

www.antislavery.org

Abolition was achieved only after a prolonged political struggle over decades. The legal abolition of slavery in British colonies in 1833 (initially excluding India) was eased by payments of compensation to slave-owners but not to the formerly enslaved workforce, who continued to face oppressive conditions. Hence it is possible to take a relatively cynical view of Abolition, attributing it to the weakened importance of the sugar interest for the British economy. Nonetheless, it was historically important when thousands of ordinary citizens began to lobby for the regulation of international trade and the establishment of universal human rights. The critical challenge remains, as it does today, that of enforcement of such international norms. Today’s slogan of Anti-Slavery International urges:

‘Help Us Finish What We Started’.

It’s a righteous task but still mammoth one …

[For more on this theme, see also Witnesses-19]