Georgian Witnesses

19 / PERSPECTIVES ON LONG-TERM ASSESSMENTS OF THE GEORGIAN ERA THROUGH TIME

DEEP CONTINUITIES

Time is a constant feature of the cosmos, even while human skills of time measurement have changed greatly over the centuries.

19.1 CONTINUING TIME, CHANGING TECHNOLOGIES Guildford Town Clock (1683), soaring over Guildford High Street, Surrey, as it does today.

Guildford Town Clock, made by London clockmaker John Aylward, and projecting from Guildford Town Hall since 1683.

19.2 CONTINUING TIME, CHANGING TECHNOLOGIES

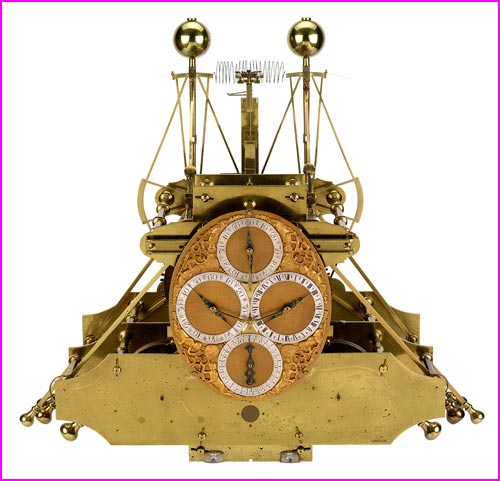

John Harrison’s prize-winning Marine Chronometer H1 (1735), the first of four instruments which he built – each one smaller and more accurate than its predecessor, for which he was eventually awarded the Board of Longitude’s prize, the sum of £5,000 being dispensed in 1763. The technology for time measurement under difficult conditions needed a mixture of ultra-precise instrumentation, plus accurate mental calculation to accommodate climatic and zonal variations and a reliance on the steady unfolding of time.

John Harrison’s Marine Chronometer H1 (1735), devised for accurate measurement of longitude when at sea: © original in National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

19.3 CONTINUING TIME, CHANGING TECHNOLOGIES

The advent of the Electric Clock (1840) brought high standards of accuracy into everyday use. There were variants of electro-static clocks in operation from 1814, using current from dry-pile batteries; and in 1840 the Scottish clock- and instrument-maker Alexander Bain patented the first clock powered by live electrical current. In 1841 he added a patent for a powered electromagnetic pendulum, which would keep the clock going without need for springs or weights. Many other experimenters were working on similar ideas and the process of improvement continued unabated, using familiar elements from earlier clocks while updating the

power base.

An early electromagnetic clock by Alexander Bain (1810 – 77), dating from the 1840s. The longcase glass-fronted housing reveals the working of the electromagnetic pendulum, reassuringly combining new technology with old familiar formats. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/

wiki/Electric_clock

SLOW EVOLUTIONARY CHANGES, UNFOLDING GRADUALLY AND OFTEN (BUT NOT ALWAYS) IRREVERSIBLY

19.4 LONG-TERM TRENDS, WHICH ARE HARD TO CONTROL OR TO HALT: THE SPREAD OF LITERACY AND NUMERACY

Skills in literacy and numeracy were – slowly and patchily – spreading across Great Britain’s regions and social classes. with men leading the way but women following in their footsteps. Critics of a conservative disposition often feared that women, servants and the lower orders generally would become too ‘uppity’ if they gained skills beyond their ‘lowly station’ in life. Yet that viewpoint was increasingly hard to maintain publicly, given public praise for ‘light and learning’ and the Protestant emphasis on being able to read The Bible. Thus the spread of learning and skills, supported by accessible education, plentifully available reading matter, economic utility, and social approval, was becoming a cumulative trend. No society (to date) that has gained mass literacy and numeracy has subsequently lost it. Instead, human skills and potential are being unlocked – with complex and still unfolding political, economic, social and cultural effects.

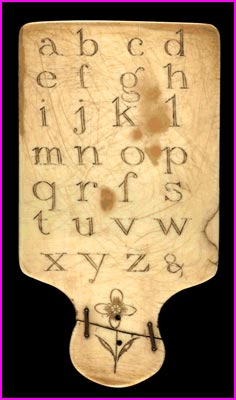

English Eighteenth-Century Ivory Hornbook, devised as a memory-aid for children, with the alphabet in upper-case letters on one side and (shown here) lower-case letters on the reverse. Note that the list includes the elongated version of lower-case ‘S’, as well as the compact ‘s’ which was rapidly becoming standard. © original in US Library of Congress No = 2007700155

19.5 LONG-TERM TRENDS, WHICH, IN THE CONTEXT OF FAVOURABLE ECONOMIC CIRCUMSTANCES, ARE HARD TO CONTROL OR TO HALT: URBANISATION

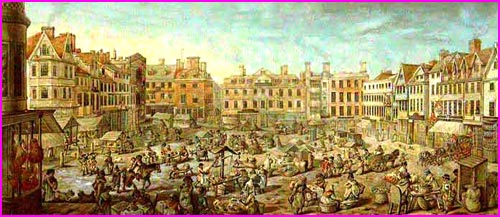

By 1851, Great Britain was the first large region of the world to have over half its population living in sizeable towns – with the urban population continuing to grow thereafter as a proportion of the total. It was a trend which proved to be a portent of global urbanisation, now apparent world-wide. But, far from meaning that towns have spread to cover the globe, the process entails a marked regional specialisation, with extensive areas of land devoted to producing food and resources for the town populations, which grow by recruitment from the countryside as well as via their own reproduction. Meanwhile the towns specialise (variously) as industrial centres, ports, dockyard towns, commercial/ professional hubs, resorts and entertainment centres, capital cities, and local market towns. It is an interlocking process that has (to date) proved irreversible. Its leaders are the world’s urban/industrial economies, yet these are potentially vulnerable should their global supply chains be seriously disrupted.

Norwich Market Place (1799), by Robert Dighton. This energetic picture shows the bustling business required to provide food, drink and resources for an established urban/commercial/ social hub like Norwich. The city’s growth was marked in its array of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century housing and shops surrounding the central market place, where both urban and country traders gathered for business. In fact, the fortunes of Norwich changed in the early nineteenth century as its staple textile industry was eventually displaced by the newly mechanised worsted weaving industry of Bradford and its environs. Yet Norwich did not decline out of urban existence but continued, with a slower pace of growth, to perform its role as a significant commercial and regional hub, as it remains today. © wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Robert_Dighton_

Norwich_Market_Place

19.6 LONG-TERM TRENDS, WHICH, IN DEMOGRAPHICALLY SUITABLE CIRCUMSTANCES, ARE HARD TO CONTROL OR TO HALT: POPULATION GROWTH

Overall population growth in Great Britain and Ireland, especially in Ireland before the Great Famine (1845 – 72), was surging during the long eighteenth century. And that process was part of what has become an accumulating worldwide trend since circa 1700. Clearly there have been many world-regional variations within that trend, the experience of Ireland, which has not yet recovered to its pre-Famine population total, being a melancholic reminder of

that point.

The causes of the global explosion of the human population are linked to the abeyance of great pandemics like the Black Death, as well as advances in medical intervention, such as inoculation and then vaccination against the ravages of smallpox, which all helped to bring down death rates, including child mortality; while another set of interlocking causes have raised birth rates, especially via falling ages at first marriage in towns – and the urban decline in the proportion of the population never marrying.

By 1798, the global rise in population had already generated a penetrating critique from Thomas Malthus (1766 – 1834), who warned that rampant demographic growth would tend to expand beyond the world’s resources to feed and sustain such a population. In fact, expanding production has so far averted a global Malthusian crisis (though there have been many regionalised disasters) but the global need to control runaway population growth is generally acknowledged; and pandemics repeatedly underline human vulnerability.

Detail from Characters and Caricaturas (1743) by William Hogarth (1697-1764), a Londoner who painted these contemporaries from life, in England’s fast-expanding metropolitan region which by 1800 had become one of the largest cities in world. © https://publicdomainreview.org/

collection/characters-and-caricaturas

-bywilliam-hogarth-1743

DRASTIC, SUDDEN AND REVOLUTIONARY CHANGES TOOK PEOPLE BY SURPRISE, HAD A HUGE IMPACT AND AGAIN WERE OFTEN BUT NOT INVARIABLY HARD TO HALT

OR REVERSE

19.7 UNLEASHING BRITISH MILITARY & NAVAL POWER OVERSEAS, FIGHTING WARS, PROTECTING TRADE AND ESTABLISHING COLONIES GENERATED AN INFORMAL ‘MARITIME’ OR ‘TRADING EMPIRE’. BY 1801, HOWEVER, REFERENCES TO ‘THE BRITISH EMPIRE’ BECAME MORE COMMON, ALBEIT WITHOUT A BRITISH EMPEROR

[In 1876, Queen Victoria was made Empress ‘of India’, not of Britain or a British Empire]

Supports for British Power Overseas: (L) drawing of Petty Officer in Royal Navy (c.1799); (Centre) the British East India Company’s trading toe-hold at Fort St George on Coromandel Coast, Madras, India, as depicted by Jan van Ryne (1712 – 60); (R) Grenadier Guard in the British Army (c.1799).

Great Britain in the eighteenth century shared prominently in Europe’s ‘outward’ expansion, as Russia marched East towards the Pacific, and leading Atlantic seaboard powers, including Britain, France, Spain and Portugal, gained overseas settlements world-wide. It was a mark of both British and European cultural confidence yet also political aggression vis-à-vis the ‘colonised’ indigenous peoples. Relationships thereafter evolved in many different ways, involving deep mutual cultural exchanges as well as exploitation and bloody conflicts. First of the British colonies to declare Independence (1776) were the Thirteen that became the new United States of America (ratified 1783); the last substantial region to achieve Independence being India (1947). Britain’s ad hoc conquests later hardened into formalised imperialism – with both conservative and liberal would-be justifications. Yet anti-imperialism (and some constitutional innovation) also emerged, not only in the colonial territories but also within Britain. Big revolutionary changes thus have major impact but can also be subsequently redirected (rather than simply reversed).

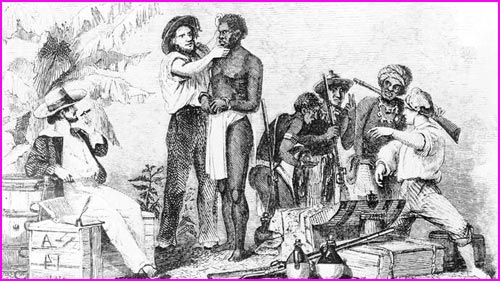

19.8 USING BRITISH WEALTH & MARITIME POWER TO TRADE IN AFRICAN CAPTIVES (UNTIL 1807) AND TO SUPPORT COLONIAL SLAVERY (UNTIL 1833)

Between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries, some 12.5 million captive Africans were traded into slavery in the New World by the major European powers of the Atlantic seaboard and also (after 1776) by American traders. It is the largest case of enforced migration in global history, and its complex ramifications are still unfolding. Britain did not invent either slavery or the trade in captives; but from the later seventeenth century onwards, it used its commercial wealth and naval power to participate on a mass scale. British goods were sold to African dealers, who supplied captives; the African captives were transhipped across the Atlantic, with horrendous death rates on the trade’s notorious ‘Middle Passage’; and then those surviving were sold into slavery in the New World, in exchange for valued raw goods, notably sugar, cotton and tobacco. All these transactions pre-1807 were carried out legally. Profits and raw materials from the triangular trade permeated throughout the economy, while most Britons saw nothing of the underlying business.

European Merchants and African Dealers Trading in Captive Africans: legally but, as political opinion slowly but increasingly declared, immorally from Captain Canot: Or, Twenty Years of an African Slaver (New York, 1854).

What became known as the ‘slave trade’ raised fundamental questions of human morality. Britain’s Quakers – a religious minority with a staunch belief in equality – were among the first to protest; and, slowly, Abolitionist campaigners strove to alert public opinion and to pressurise governments (for details, see Witnesses-12). Thus, while Britain’s role in the triangular trade was one great innovation, it generated a seismic counter-movement, which eventually won. In 1807 Britain abolished the slave trade, rendering such dealings by its merchants as illegal under British law; and it sent the Royal Navy to patrol the high seas in an attempt to halt all other slave-trading activities by other nations. In 1833, furthermore, Britain abolished slavery in all British colonies (excluding initially India, where similar reforms followed from 1843 onwards). There were serious practical limitations to such policies. They did not address problems faced by the transported Africans and their descendants. Nonetheless, the Abolitionists launched a policy now adopted world-wide. In 1948, the United Nations’ Declaration of Human Rights explicitly outlawed slavery and neo-slavery everywhere. It remains now to enforce the Declaration; and to remedy current and historic harms.

19.9 FOSTERING A CULTURE OF EXPERIMENTATION, HARNESSING STEAM AS A NEW SOURCE OF POWER AND EXPERIMENTING WITH ELECTRICITY AS ITS

COMING SUCCESSOR

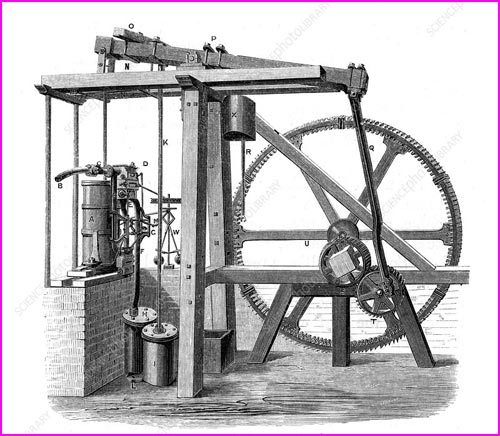

Technological change has proved an all-conquering force. Yet the pathways of change include failed trackways as well as successes – and great changes often need social as well as state regulation to mitigate or control great unforeseen side-effects. High-intensity interactions between the three kingdoms within eighteenth century Great Britain and Ireland fostered a lively culture of scientific experimentation – one that was also embedded within a shared set of ideas and investigations, especially in western Europe and in North America. The steam engine patented in 1769 by James Watt (1736 – 1819) built upon earlier experiments and was further refined when put into industrial production. It was in 1788, when observing the process of technological transfer, as new machinery initially used in cotton-manufacturing was adopted to mechanise the manufacture of woollen textiles, that the perceptive commentator Arthur Young observed succinctly:

‘A revolution is making’

Model of an Early Steam Engine, revealing the high-calibre metals and precision engineering needed to create the ‘workhorse of the Industrial Revolution’. © Science Photo Library

Moreover, the processes of invention were incremental. At the same time, experimenters like Joseph Priestley (1733 – 1804) were seeking to harness the power of electricity: unlocking nature’s secrets was exhilarating for the first pioneers – and the accumulating achievements of techno-science and its industrial applications have left humanity with a mighty long-term mix of blessings and deleterious side-effects (climate change; air, light and water pollution etc.) which are urgently in need of collective attention.

19.10 COMPOUND IMAGE SHOWING OVERLAP BETWEEN FORCES OF CONTINUITY, GRADUALISM, AND REVOLUTIONARY CHANGE

Shown as headcode for GW19 (above), this striking image, created especially for Georgian Witnesses, combines the Guildford Town Clock (19.1), representing the constant presence of time; the Alphabetic Hornbook (19.4), plus a flowing river of letters, indicating the cumulative spread of literacy; and James Watt’s revolutionary steam-engine (19.9).