Georgian Witnesses

15 / ADVENT OF GEORGIAN WORKERS, INSTANCED BY INDUSTRIAL DISPUTES, RADICAL CAMPAIGNERS AND A SATIRICAL SONG

THREE DIFFERENT METHODS OF WORKER RESPONSES

15.1 ORGANISED TRADE UNIONISM

Many Georgian workers joined self-help saving clubs, book clubs and the like, among which were numerous early trade unions, known as ‘combinations’, which focused upon improving pay and working conditions. Sometimes relationships between employers and combinations were harmonious; but far from always.

One of many serious industrial confrontations occurred in Calton, just outside Glasgow, in summer 1787. Numerous weavers went on strike, marching in processions through the Glasgow streets, in protest at a proposed sizeable cut in rates of pay. Strikers cut the weavers’ webs on the looms of those still at work, and sacked a warehouse, burning the contents. That escalation allowed the magistrates to summon the troops, who, after a considerable struggle, suppressed the riot, six weavers being killed in the process. In 1788 a weaver named James Grainger, who was considered to be a ringleader, was prosecuted and found guilty of forming an illegal combination; he was then sentenced to a public whipping and to self-banishment from Scotland for seven years. Grainger later returned and participated in the big 1811 – 12 industrial disputes in Glasgow.

William Pitt’s government in 1799 and 1800 outlawed all industrial combinations; but the effect was to drive some forms of industrial protest underground as well as to generate resentments, prompting the repeal of the ban in 1824, followed by a tightening of controls (albeit short of a complete ban) in 1825.

A memorial plaque to Calton’s slain weavers in 1787 was posted in 1987 in Glasgow’s museum/cultural centre, known as the People’s Palace, Greens, Templeton St, Glasgow G40 1AT.

15.2 ANONYMOUS THREATS

One potential weapon especially for a disgruntled individual, feeling otherwise powerless and socially embattled, was secretly to deliver an anonymous threat, in suitably blood-curdling terms. This tactic was used in both Georgian towns and countryside; and has a new salience in the twenty-first century, as online anonymous threats and trolling are daily demonstrating how worrying anonymous threats can be – the very fact of anonymity unleashing a secret venom which is usually held in social check.

Having analysed over 300 such letters dating from the eighteenth century, historian E.P. Thompson found that a percentage involved blackmail (pay this sum or face that penalty) while many complained about specific social grievances, such as the cost or shortage of bread; or industrial disputes relating to rates of pay, or wider grievances such as those relating to the enclosure of common land, or the operation of the poor relief system.

The use of letters – even if many were roughly written – indicated the spread of literacy through all social classes. The language of threats was vivid, with references to death and bloodshed, often with references borrowed from The Bible, such as this threat issued to a master shipwright in the Chatham Dockyards in February 1764:

‘You will be very soon Nock’t out of the Book of Life …

You are like the rich Man wich refused to give

Lazarus the Crums which fell from his tabel’.

Another bitter complaint about high food prices in Birmingham in March 1767 used a crafted mixture of threat and civility, on the one hand threatening a mass turnout of poor men, ready to fight and to burn down the Parliament-House;

but ending:

‘We desire you to put it [their complaint] in the News Paper immediately or we will burn down your House, I’ll be damned if we don’t; but, if you put it in the

Paper, we shall be greatly obliged

to you’.

All anonymous threats helped to spread a degree of social tension not only among the letters’ recipients but also within the wider society. Anyone seeking official help in detecting the perpetrator was required to post the letter verbatim in the London Gazette [the government’s leading official journal of record], which also published the promise of a reward and a pardon for anyone helping to reveal the author. These anonymous threatening letters revealed that, in Britain’s highly unequal society, some of those at the ‘foot’, who were unhappy with their lot in life, took the opportunity of venting their anger in personal terms, against named individuals. Such actions were not winning moves in the course of disputes, instead adding to social tensions. At the same time, however, such threats gave pointed personal reminders to those at the ‘top’ that they could not entirely ignore the masses. The classic source for this subject is the essay by E.P. Thompson, with research assistance from E.E. Dodd, ‘The Crime of Anonymity’, in D. Hay, P. Linebaugh, J.G. Rule, E.P. Thompson and C. Winslow, Albion’s Fatal Tree: Crime and Society in Eighteenth-Century England (1975; 2011), pp. 255 – 308 and Appendix, A Sampler of Letters, pp. 309 – 44. Extracts quoted from pp. 274 and 325 – 6.

There is no monument to those who make anonymous threats but the tradition is a living one, as the contemporary use of Twitter constantly reveals.

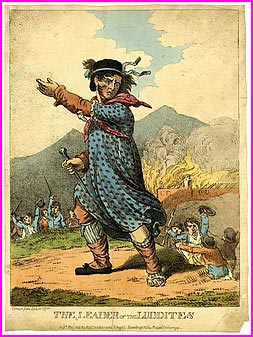

15.3 ‘LUDDITE’ MACHINE-BREAKING

Breaking machinery or other physical objects of popular displeasure in the course of an industrial or social dispute was not a new phenomenon in the early nineteenth century. Yet machine breaking and its associated name ‘Luddism’ gained an enduring notoriety from the actions of secret societies of textile workers in Nottinghamshire and other textile areas between 1811 and 1816. Angered by high food prices and industrial dislocation, they met in secret night-time gatherings outside the towns; they too sent threatening letters; and, above all, they broke the new mechanised stocking- and lace-making frames, which, with their greater speed and efficiency, were replacing the traditional frames and reducing employment among traditional workforce.

Their legendary leader was one Ned Ludd, seemingly named after a framebreaker in 1779; he was depicted as an outlaw figure, sometimes lightly disguised as a woman; as shown in a famous engraving (1812) entitled

The Leader of the Luddites.

The government responded with a mixture of legal and military repression, notably with the Frame-Breaking Act of 1812 (re-issued 1817), which made capital offences of frame-breaking, frame-damaging, and entering a property with intent to damage a frame. A lone voice of opposition in Parliament came from the youthful Lord Byron (1788 – 1824), who spoke against the 1812 Act in his maiden speech in the House of Lords and deplored the ‘squalid wretchedness’ of the lives of unemployed weavers in

the Midlands.

By c.1817, the Luddite movement had subsided. Some 60 – 70 Luddites were hung; others transported. Their collective name, however, has resonantly survived. It is used as a way of criticising technophobes. But it is also used positively by groups known as Neo-Luddites, who campaign against the dangers of rapid technological change. The original Luddites were not themselves against technology ‘as such’; but were highlighting what has become a chronic problem for workers, potentially world-wide, when changing technologies and/or the changing location of jobs can throw large numbers of people out of work, through no immediate fault of their own, especially when they lack the protection of social welfare programmes and alternative

job opportunities.

Memories are kept alive by the Ned Ludd Society (founded early C21?): https://www.facebook.com/

nedluddsociety

and by contemporary neo-Luddite campaigns, for example

against drones.

PLUS FIVE DIFFERENT CAMPAIGNERS FOR A NEW SOCIAL AND/OR POLITICAL ORDER

15.4 AN ADVOCATE FOR AGRARIAN COMMUNES

Thomas Spence (1750 – 1814), from a poor background in Newcastle upon Tyne, was an inveterate campaigner, writing not only popular tracts but also popular songs to convey his political philosophy to the masses. He advocated the common ownership of the land, equality between men and women, and care for the rights of infants. He also advocated spelling reforms to make the acquisition of English easier for the uneducated. Spence explained his basic cause in 1775, with the pamphlet Property in Land is Every One’s Right.

And he drew on that theme for this characteristic Spencean song: Touch-Stone of Honesty (c.1807), to be sung to the well-known tune of Lillibullero. Spence explained what he saw the great gulf between powerful landowners and the rest of the population:

‘Ye Children of Woe, attend to my Song,

We’ve found out the Rogues, who did us the Wrong,

Who shackled the World o’er since it began,

And liv’d on the Blood of poor suffering Man.

This Striving for Fields such Villainy yields

No [private] having of Lands should we suffer at all.

To get or to hold, you need not be told,

Transforms Landowners to Judases all’.

[Judas being the ultimate symbol of betrayal].

By highlighting the issue of landownership, Spence contributed to an emergent tradition in Britain, calling for land reform, and raising the issue of redistribution of income and capital assets. With Thomas Paine, Spence was one of the first to call for a universal basic income.

What kept him going? Despite his political isolation and lack of success, being twice imprisoned for his political views, Spence remained a resolute and cheerful figure buoyed by his vision and his songs, living in a cultural world of his own, as was eminently possible within the great sprawling metropolis of London. (There are parallels with small radical religious groups in the metropolis, and with the life of William Blake, a near contemporary, who also nursed his own vision). Spence thus held up an alternative mirror to Georgian society and did so with a barrage of songs as well as political tracts.

15.5 THE RADICAL ORGANISER

Thomas Hardy (1752 – 1832), an artisan shoemaker, was the son of a Scottish merchant seaman who died when Hardy was a boy. The young Hardy moved through several jobs before settling in London, where he learned to make shoes as a journeyman boot-and-shoe-maker before prospering modestly enough to open his own boot-and shoe-shop in Piccadilly in 1791.

In 1792, he founded, initially with nine friends, the radical working-class London Corresponding Society, dedicated to campaigning for the universal (male) suffrage. It was not the first body to make such a call; but it was the first led and organised by working men, on the frontier between what would later be called lower middle-class and working-class society. As the first Secretary, Hardy was the linch-pin organiser, collating the activities of all the LCS London branches, and of the parallel working-class Societies established in provincial centres, like Manchester, Norwich, Sheffield and Stockport. Recruitment was rapid, with members including Thomas Paine, Thomas Spence, Olaudah Equiano and countless others among the ‘lower orders’. Hence when in 1794 the government of William Pitt panicked and put the leaders of the LCS on trial for High Treason, Hardy was one of those whose books and papers were seized, while he was thrown in the Tower of London. It was also a moment of personal tragedy for Hardy, whose wife was attacked in their home by a loyalist pro-government crowd – and subsequently died in childbirth. (The couple already had five children, all of whom had died young).

In the event, Hardy was the first to be acquitted by a London jury, which decided that the evidence did not support a charge as heinous as High Treason. Hardy remained active in the LCS, but the government moved to suppress the movement by legal constraints rather than by individual court cases; and by the end of the 1790s the movement was in abeyance. Hardy lived an inconspicuous life thereafter, working as a shoemaker in London; remaining in touch with radical friends via letter-writing; supporting various radical good causes; and writing regularly to the London papers under the pseudonym ‘Crispin’. Thomas Hardy was one of the quiet, self-effacing but effective organisers that movements need, and he never wavered in his commitment to reform, even after the mass campaign movement

had collapsed.

What kept him going? A stubborn tenacity; contacts with a network of like-minded friends; a confidence in the coming rights of man; and a strong Presbyterian faith (many of those who testified for Hardy at his trial were members of the Scottish kirk that he attended in London), which gave Hardy a personal independence, and an inner light which did not depend upon validation from others.

[NOTE: Hardy was acquitted on the charge of Treason but in 1793/4, five radical democrats, two from Scotland and three from England, were convicted of sedition in Edinburgh and sentenced

to transportation.]

A magnificent 90 foot (27m) obelisk as monument to the five men – Joseph Gerrald, Maurice Margarot, Thomas Muir, Thomas Fyshe Palmer and William Skirving – was erected in 1844 on Calton Hill, Edinburgh EH7 5AA, by a later generation of parliamentary reformers; and a similar, but less grand, monument to the Political Martyrs was erected in 1852 in Nunhead Cemetery, South London SE15 3LP.

In general, the campaigns for the democratic franchise, in the 1790s, the 1830 – 40s, and the later nineteenth century, did not dwell on their antecedents, but these two monuments were exceptions, fired by the injustice of both the charge and the conviction.

Two Monuments to the Political Martyrs in the Cause of Democracy (1793), erected by Victorian reformers (L) on Calton Hill, Edinburgh (1844); and (R) in Nunhead Cemetery, South London (1852).

15.6 THE RADICAL ORATOR AND COMMUNICATOR

John Thelwall (1764 – 1834) was a lifelong friend and political ally of Thomas Hardy (see above 15.5), although Thelwall’s outlook was secular, and his style dynamic and extrovert. Thelwall’s own social position was marginal, between middle-class respectability and the working-class ‘culture of expediency’, following the financial failure of his London silk merchant father. (For fluctuations in middle-class fortunes, see Witnesses-14). From the age of 13 onwards, the young Thelwall had a series of unsuccessful apprenticeships, in tailoring and in an attorney’s office, as well as attending medical lectures at leading London hospitals, before embarking on a freelance career as a writer and journalist.

In 1794 he was a prominent activist in the London Corresponding Society, being, with Thomas Hardy, one of those thrown in the Tower, at the age of 30, on a charge of High Treason. Thelwall’s gifts as an orator made him a potent figure and, after his release in the wake of Hardy’s acquittal, Thelwall continued to tour the country, giving political lectures under the guise of commentaries on classical Roman history – a tactic to elude the censorship under Pitt’s Gagging Acts of 1795.

[The Treason Act and Seditious Meetings Act (both 1795) were devised to curb meetings of radical societies, such as the LCS. The first Act extended the definition of Treason, while the second restricted the size of public meetings to 50 people or fewer; and specified that all places like lecture halls, where political discussions were held, required a magistrate’s license – and, without that, meetings were liable to punishment as seditious

and disorderly.]

One person, who heard Thelwall lecturing in Norwich in June 1796, was a young trainee lawyer of conservative views. He liked Thelwall’s argument well enough but not his style of delivery, writing in a private letter: ‘He raves like a mad Methodist Parson; the most ranting Actor in the most ranting Character never made so much Noise as Citizen Thelwall’. Amyot’s reference to ‘Citizen’ was sarcastic, that appellation being common among young radicals and admirers of the French Revolution.

[See Thomas Amyot to Henry Crabb Robinson, 8 June 1976, in P. J. Corfield and C. Evans, Youth and Revolution: Letters of William Pattisson, Thomas Amyot and Henry Crabb Robinson (Stroud, 1996), p.138

In 1797, Thelwall abandoned his lecture tours, which had been from time to time accompanied by rumbustious scenes from hostile crowds. In summer that year, he made a celebrated visit. followed (unbeknown to him) by a Home Office spy, to the young poets, S.T. Coleridge and William Wordsworth, then living in Somerset. Thelwall thus himself constituted a direct personal link between radical politics and the (then) radical intelligentsia.

Inspired by their joint conversations about combining an alternative rural life with projects for cultural renewal, Thelwall retreated to a small farm in the tiny village of Llyswen, on the banks of the River Wye, near Brecon LD3 0UY, in mid-Wales, where he continued to write but also threw himself into hands-on farming, with characteristic energy. Thus he confided to Thomas Hardy by letter in January 1798:

‘I dig – I cart dung & Ashes – I thresh in the Barn – I trench the meadows when

the fertilizing rains are falling, … – In short the political lecturer of Beaufort

Buildings [his London residence] is a mere peasant in Llyswen; & you would

smile to see me in an old thread-bare jacket – a pair of cloth pantaloons rudely

patched, & a silk handkerchief with my spade & my mattock trudging thro’ the

village or toiling on my farm.’

[Quoted in P.J. Corfield, ‘Rhetoric, Radical Politics and Rainfall: John Thelwall in Breconshire, 1797 – 1800’, Brycheiniog, Vol. 40 (2009), pp. 17 – 36]

In August 1798, Coleridge, Wordsworth and Dorothy Wordsworth visited the Thelwalls at Llyswen on their own tour up the Wye – the highspot of their collective friendship. His hands-on farming contrasted with their more genteel rural retreats, and in time the friends also diverged politically. In 1801, Thelwall, with his wife and remaining children, abruptly quit Llyswen and their rural lifestyle, saddened by the sudden death of his oldest daughter Maria. The agricultural experiment had not been a success, marred by years of exceptional rain which blighted crops in the field; while the comparative rural isolation had not suited the sociable Thelwall.

He continued thenceforth with his political journalism, his poetry, his lectures, and his optimism; but was no longer a front-line activist in radical working-class circles. Thelwall instead put his energies into making a successful living as a speech therapist, helping those with speech impediments – giving a voice to the literally voiceless or

vocally-challenged.

What kept Thelwall going? His energy, optimism and self-belief were partly innate; but he also believed in finding local and immediate solutions while waiting for big long-term historical trends to take effect. ‘Whatever presses men together’, he wrote in 1796, ‘… though it may generate some vices, is favourable to the diffusion of knowledge, and ultimately promotive of human liberty. Hence every large workshop and manufactory is a sort of political society, which no act of parliament can silence, and no magistrate disperse’. In the meantime, citizen activists should do their best to advance democratic thinking by all peaceful means, taking small steps locally and practically, depending on the circumstances …

15.7 THE RADICAL TRADE UNIONIST

The radical trade-unionist and factory reformer, John Doherty (1798 – 1854), was born into a poor family in County Donegal, Ireland, and, at the age of 10, was set to work locally as a cotton-spinner. By the age of 16, he had moved to Manchester, at the heart of the booming cotton industry; and by 1818, at the age of 20, he was active in a big spinners’ strike – and was gaoled for two years. Doherty was undaunted in the cause of trade unionism and by 1828 he became leader of the Manchester Spinners’ Union. However, his ambitious plans for a General Union of Cotton Spinners, including spinners in Scotland and Ireland, failed. And an even more ambitious scheme, for a National Association for the Protection of Labour, also collapsed, reflecting the difficulty of coordinating workers in many separate industries. Thereafter, Doherty withdrew from direct labour organisation. But he made a living as a bookseller and printer, publishing a radical journal The Voice of the People; and keeping a free reading area in his shop, as an impromptu library. After another spell in prison following a libel action, Doherty became an assiduous campaigner with Robert Owen. for factory reform and improvements to working conditions, culminating in the 1847 Factory Acts.

What kept Doherty going? Little is known of his private motivation; but he clearly ‘thought big’; moreover, his determination kept him going, despite some aspersions on his character from opponents, and despite some anti-Irish feeling among his fellow-workers. Doherty evidently believed that his own skills of literacy should be used to help others, as indicated by the title of his journals The Voice of the People (1832) and The Poor Man’s Advocate (1832/3). Furthermore coming from Ireland, Doherty had an outsider’s sense of the need for ecumenicalism and workforce solidarity, even though these things were not easy

to achieve.

15.8 THE IMPROVISOR, PROMOTING WORKING-CLASS BENEFIT SOCIETIES, TRADE UNIONISM AND PARLIAMENTARY REFORM

John Gast (1772 – 1837), born in Bristol, moved to London where he became a shipwright (ship-builder), in the Deptford shipyards in south-east London – working at an occupation which was not glamorous but was both skilled and respectable. One of the first organisations with which he was identified was the Hearts of Oak Benefit Society (founded 1802), enabling workers to pay regular subs into a communal fund, which then provided sick pay in hard times (Hearts of Oak being a reference to the oak-built ships of the Royal Navy). As a trade unionist, Gast was also involved with the 1822 attempt at establishing a Committee of the Useful Classes (note the adjective!), which hoped to achieve pan-national coordination between Britain’s many trade unions (as attempted also by Doherty in 1828) – see above 15.7. The repeated difficulties at coordinating many different trade unions were acknowledged in 1868, when the Trades Union Congress adopted a federal constitution rather than seeking a unitary institution. In 1836 Gast was among the founders of the London Working Men’s Association, which drafted the core Six Points of the People’s Charter, forming the basis of Chartism in the 1830s and 1840s. This campaigning movement, in favour of the adult male suffrage, drew from the energies and organisation of trade-unionism, but it also recognised that workers without the vote were waging a losing battle. (And, even with the vote, their interests are still debated and disputed).

What kept Gast going? For a time, he was a publican in working-class Deptford, which kept him in touch with local opinion. And he was a Nonconformist lay preacher, which contributed to Gast’s noted sincerity of speaking style, and to his willingness to stand up and bear witness. His empirical readiness to try different forms of organisation testified to his quest for unity as a source of strength – confirmed by the name of his proposed ‘Philanthropic Hercules’ (1818), or workers’ alliance – providing mutual aid from collective strength.

PLUS AN ANONYMOUS SONG HERALDING THE ADVENT OF THE WORKING-CLASS (1795)

For some years, there were scattered references to the ‘industrious class’ and ‘laborious class’ as well as ‘lower class’, before ‘working class’ was first used in 1789 and within a generation had come to stay. This usage is a ‘near miss’.

15.9 Wholesome Advice to the Swinish Multitude (1795), sung to the tune of

‘Mind, hussy, what you do’:

‘You lower class of human race, you working part I mean,

How dare you so audacious be, to read the works of Paine?

The Rights of Man – that cursed book – that such confusion brings,

You’d better learn the art of war – and fight for George our king.

Chorus:

But you must delve in politics, how are you thus intrude?

Full well you do deserve the name of swinish multitude.

There’s the labourer and mechanic too, the cobbler in his stall,

Forsooth must read The Rights of Man, and Common Sense and all.

For shame, I desire ye wretched crew, don’t be such meddling fools,

But be contented in your sphere, and mind King Charles’s rules.

Chorus: But you must delve in politics [etc]

… Altho’ it’s from our blessed king that all these blessings flow,

Altho’ you sing you need no king, because Paine told you so;

But Reformation’s all your cry – and if you keep this rout,

Then you shall have the rights of swine – that’s a ring within your snout.

Chorus: But you must delve in politics [etc]

I pray be wise, and don’t despise this kind advice of mine,

Your name regain, and not retain the filthy name of swine;

Let Government do what they please, then you’ll be free from harm;

For when a Constitution’s pure – what needs there a reform?

Chorus: So no more delve in politics, no longer thus intrude,

And not incur that filthy name of Swinish Multitude.

[Lyrics from J. Holloway and J. Black (eds), Later English Broadside Ballads

(1975), pp. 278 – 9. The title alluded to Edmund Burke’s contemptuous

dismissal of lower-class involvement from his Reflections on the French

Revolution (1790) – as earlier cited under 11.5.

The verses make reference to the works of Thomas Paine, the leading political theorist of democracy (albeit limited to the adult male suffrage), including especially The Rights of Man (1791/2) and his earlier Common Sense (1775/6). The cryptic reference to ‘King Charles’s rules’ probably alluded to the legal maxim that ‘the king can do no wrong’. In context, it means (ironically) that the populace should mind the traditional rules of obedience and deference. This song’s tone is sarcastic throughout – lampooning right-wing propaganda – but it could inadvertently arouse further suspicion, by implying that working-class political activists must have republican aims. In fact, the London Corresponding Society steered clear of any republican declarations, because they wished to focus upon franchisal reform, and also because they were already facing a backlash from worried upper- and middle-class opinion.