Georgian Witnesses

17 / IMAGES OF GEORGIAN WORKPLACES, WITH ICONS OF TWO GREAT ENGINEERING FEATS AND A LITERARY WARNING

CONTEXT

Needless to say, some workers were idle and/or ineffective. And plenty of businesses were badly managed. Yet the workshops, large and small, were the seedbeds not just of experimentation but also of technical applications and refinements once inventions were introduced. Scientific and technical advances depended on the work of scientists and inventors; the availability of coal and iron; plus an ever-expanding demand – not only from domestic consumers but also from industrial, commercial and state buyers. Meanwhile, the increasingly literate and numerate workforce, with a willingness to adapt and experiment, also played a crucial role. As the railway engineer George Stephenson once remarked, it took a nation of experimenters and engineers to produce a

steam locomotive.

NINE GEORGIAN WORKPLACES

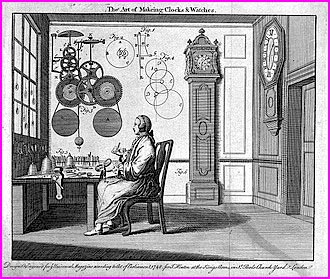

17.1 A Watchmaker’s Workroom, London (1748): the technical nature of the job requiring a clean and tidy workspace, with good natural lighting. This master craftsman is comfortably dressed, in gown and slippers, working in an airy panelled room, with examples of his wares around him in the form of a standing longcase (grandfather) clock and a wall-mounted large frame clock (both set to the same time). He is at the head of a long supply chain of workers, many living outside London, who produce the components that make his clocks, including dials, clock wheels, pendulum weights, glass faces, etc. Clocks and watches were everywhere in demand, with commercial industrial, navigational and personal users.

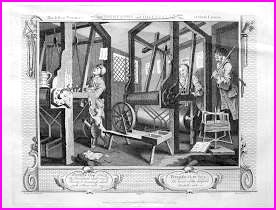

17.2 William Hogarth’s Industry and Idleness, Plate 1 (1747): the young apprentices are sharing a workroom, and, as no doubt happened often enough in real life, one is working industriously, while the other is snoozing, a fragment of a novel pinned on the handloom behind him, a jug of beer resting on the frame of the loom before him, and, at his side, a cat playing with the shuttle which has fallen unnoticed from his hand. Meanwhile, the master weaver peers into the room, ready to praise the industrious apprentice and to chastise sternly the idle fellow.

The room is dominated by the large wooden looms, where the weavers constantly extend the woven fabric, winding it onto the huge cylinders below. Weaving for long hours was tiring and monotonous work, though the workroom had to be clean and tolerably light; and it was possible for weavers to share ideas about patterns and designs, as well as to chat, to debate ideas, to read (if weaving a plain textile with no complicated pattern), to grow flowers in window-pots and to keep caged canaries.

[That pastime was traditionally popular among weavers in Norwich; and that City’s football team to this day keeps the nickname The Canaries].

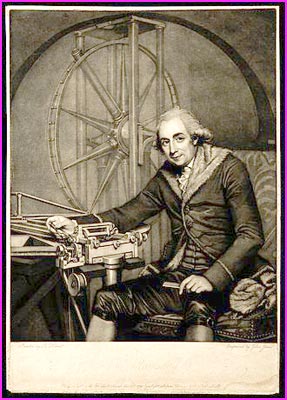

17.3 Mezzotint of Scientific Instrument-maker Jesse Ramsden (1735 – 1800) by J. Jones after Robert Home (1790), showing the celebrated Yorkshireman who made high-quality precision instruments for astronomers, surveyors, navigators, opticians, and scientists. Again the work-place has to be orderly and free from dirt and disturbance. In this image, Ramsden is shown wearing a furcoat, which was not by any means his normal working gear, but this detail was added by the artist, in order to commemorate an order made for Paul I, Czar of Russia.

17.4 Yorkshire Cloth Dressers’ or Croppers’ Workshop, from G. Walker, The Costume of Yorkshire (1814; reprinted Firle, Sussex, 1978), Plate 5: The Cloth Dresser; and text pp. 23 – 4, showing the workers concentrating, their sleeves rolled up, and their clothing protected by large white aprons. Their work entailed shearing the dampened cloth, to remove excess wool and fluff, after the textile had been combed with teazles. The workroom is bare, with clear light entering from an unshaded window, and industrial tools ranged handily. Interestingly, an older worker leans in the doorway, confirming the role of the workplace as a hotbed for news and debates as well as the sharing of work practices.

The commentator in 1814 reported that: ‘an able workman will earn great wages; and, if industrious and steady, is certain to make his way in the world’. Yet he considered the majority to be ‘idle and dissolute’, which he attributed – with a minimal flash of sympathy – to the hard labour entailed by their work; but also to their working in association with others, ‘a circumstance always injurious to morals’. Hence the employers’ interest in the process of mechanisation, which increased employer control but, conversely, reduced scope for input and initiative from the workforce.

17.5 The Bersham Ironworks, near Wrexham, North Wales [Engraving by Wilson Lowry after George Robertson, owned by Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust]:

http://old.wrexham.gov.uk/english/

heritage/bersham_ironworks/

making_iron.htm

This image unmistakeably indicates that not all workplaces were neat and clean. The huge scale of the area around the furnace dwarfs the individual workers, who work at their own specialist tasks, their working time being regulated by the requirements of the manufacturing processes but without close supervision. It was here that the iron-master John Wilkinson (1728 – 1808) and his workforce perfected the boring of high-calibre cannon. By the 1790s, however, Wilkinson found the site too small for his growing operation; and, after a dispute, the works were largely razed in 1798.

Today, the industrial museum at Bersham presents light-and-sound recreation of a typical working day of an eighteenth-century foundryman. The Ironworks are open for group visits and on special open days: http://old.wrexham.gov.uk/

english/heritage/bersham

_ironworks_visitors.htm

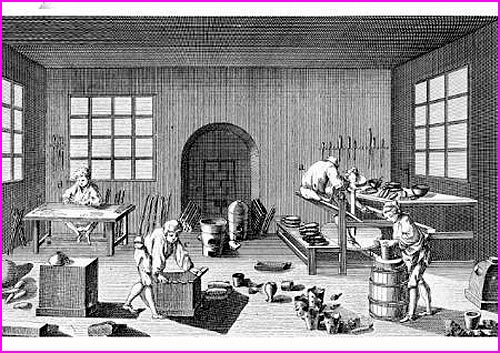

17.6 A French engraving of an Eighteenth-Century Pottery Workshop, showing the sub-division of the handcraft stages of finishing the wares to high standards of design. The workplace is light and airy; the special tools are racked carefully; and the shards of broken pottery (front centre) which have been discarded, emphasise the premium upon the careful working and handling of breakable wares. The workroom’s cleanliness and order contrast with the notorious smoke of the conical brick-built kilns, where the elegant wares were fired – as revealed by two mid-eighteenth-century Bristol plates whose frank designs (unusually) feature smoking kilns.

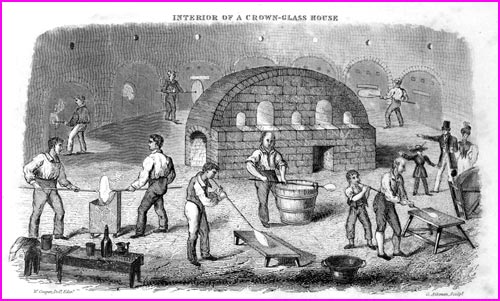

17.7 Glass-Blowing and Firing, as shown in a Scottish ‘Interior of a Crown-Glass House’, from William Cooper’s Crown Glass Cutter and Glazier’s Manual (1835):

The male workforce in this industry was accustomed to working in very high temperatures, as the glass was alternatively fired and blown. Hence the supply of liquid refreshment and pewter mugs. One of the glass-blowers is a young lad, working with a partner; others are young men, the job requiring vigorous lungs. Some visitors (R) are being shown the busy industrial scene; and, as Britain industrialised, such visits became included in tourists’ schedules. In these busy industrial workplaces, the hive of activity might at first sight seem disorderly but the specialist workforces, who all knew their own tasks, usually worked efficiently as a team, relying on one another to provide instant help in the event of an industrial accident.

17.8 Women in Industrial Employment, as shown in ‘Woman Spinning’ from Walker’s Costume of Yorkshire (1814), Plate 29, pp. 76 – 7 [cited above 17.4]. Many industrial processes were dominated by the male workforce, while women at work were characteristically employed in services – and often poorly remunerated ones at that. However, some eighteenth-century women undertook industrial labour – usually in the less skilled preparatory processes, as here. The young woman standing at the spinning-wheel is producing worsted yarn for the Yorkshire worsted weavers – a demanding task since the weavers required a

completely even yarn.

Meanwhile, the elderly lady, seated by the fire, is reeling the spun yarn with the aid of a click wheel, which clicks audibly indicating when a given length of yarn is done. A young girl helps the household by tending the fire and a large pot, containing a broth or a stockpot. All the women are plainly dressed, though they are not in rags; and the housing interior is extremely simple in its décor and furnishings. Cotton spinning – mechanised by water-power (1740s), then steam-power (1780s) – created new jobs for women in the cotton mills but put hand spinners out of work; and the same process applied later to the mechanised spinning of woollen yarn.

17.9 Artistic Recognition of the Experimental Culture: Joseph Wright ‘of Derby’ (1734 – 97) was a painter who commemorated in his art the social and industrial ambience of Derby, where he was born (a lawyer’s son) and where, after some time away, he returned to live for many years until his death. His scenes were not completely literal but drew visual attention to key themes, via striking contrasts between light and dark.

An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768) catches well the diversity of individual responses to experimentation. The young lovers (L) gaze at one another; three young men pay serious attention; one (R) is helping with the experiment; the father (Centre R) gesticulates to his young daughters, one gazing wide-eyed, the other hiding her eyes in alarm; while the central

experimenter, with his lined face, staring eyes and casual robe, could be either a fabled wizard of yore or a ‘mad scientist’ of modern times. The experiment, showing the power of air to sustain living creatures, is not immediately ‘useful’ but it is building and sharing knowledge both about biology and technology.

PLUS TWO REDOUBTABLE ENGINEERING FEATS

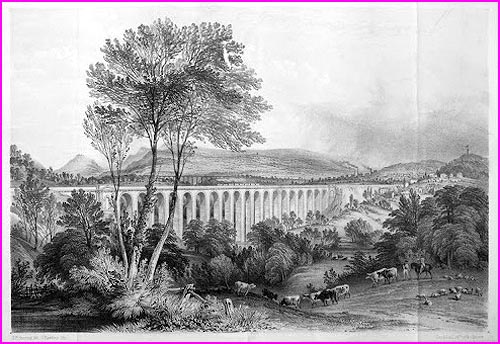

17.10 The Pontcysyllte Canal and Aqueduct crossing the Vale of Llangollen, North-East Wales. This towering eighteen-arch canal-bearing aqueduct is a Grade-1 listed building and a UNESCO World Heritage site. Designed by civil engineers Thomas Telford (1757-1834) and William Jessop (1745 – 1814), it takes the Llangollen Canal, in a cast-iron trough, across the River Dee, plus a pathway alongside the canal. The construction remains the longest aqueduct in Great Britain and the highest aqueduct in the world. It was opened in 1805, having taken ten years to design and build; and remains an engineering marvel. However, the original grand design to provide a commercial link between the waterways of the River Severn and the Mersey at Liverpool was abandoned – because the expected revenues to fund the following stages of construction never materialised.

Used for commercial traffic until 1939, the aqueduct is now, after a period of neglect, a popular destination for leisure use by canal-boating enthusiasts and walkers:

www.pontcysyllte-aqueduct.co.uk

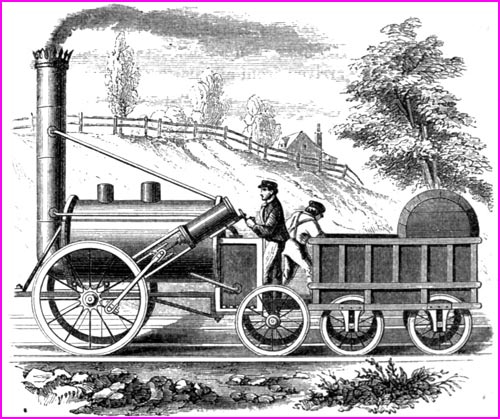

17.11 George Stephenson’s Improved Steam-Engine, The Rocket (1829), running on iron rails – as shown in antique print. The civil engineer George Stephenson (1781 – 1848) spent years refining and perfecting engines for hauling coals at Killingworth Colliery near Newcastle upon Tyne, Northumberland, before launching his own engine manufacturing company. In 1825 he drove the world’s first railway train conveying both coals and, seated in their own carriage, passengers, in a journey on the just-built Stockton and Darlington line. The first steam locomotive used on that trip, originally named Active and then known as Locomotion no 1, was technologically obsolete within

a decade.

A working replica is now on show at the Head of Steam Museum, at

Darlington North Road Railway Station:

www.head-of-steam.co.uk

George Stephenson, with his son Robert Stephenson (1803 – 59), continued to refine their models, producing in 1829 The Rocket, which won the famous railway trials held in that year and became a prototype for steam-engines over the next 150 years. Their engineering feats relied upon the availability of high-quality cast iron, cheap fuel in abundance, skilled workers to build, drive and maintain the engines and a well-drilled and reliable workforce to run the new railway system safely. Since 1862 The Rocket has been on public show, initially in London’s Science Museum and now at the National Railway Museum at York: https://www.railwaymuseum.org.uk

AND ONE FAMOUS LITERARY WARNING AGAINST UNTRAMMELLED INVENTION

17.12 The Warning:

Mary Shelley (1797 – 1851), Frankenstein: Or, the Modern Prometheus (publ. anonymously 1818; with author’s name on second edition, 1823): the book’s legendary mix of Gothic horror and science fiction, is often taken as a warning against scientific over-ambition without giving full thought to the consequences. Prometheus was the legendary figure who stole fire from the gods and gave it to mortals – with epic consequences both good and bad. His successor in this fable is experimenting with the power of electricity to spark new life … and the result was equivocal both for the experimenter, named Frankenstein, and for the ‘monster’ thus created, who is sometimes also known by his maker’s name. The novel ends with the death of the experimenter and the declaration that the ‘monster’ regrets his crimes and intends to commit suicide. Yet can it really be believed? The novel’s last sentence still leaves the ultimate fate unknown of the monstrous being, created by man but growing beyond his control:

‘He was soon borne away by the waves, and lost in darkness

and distance’.

The novel has been controversial and increasingly influential ever since its first publication, spawning in the twentieth century many films, TV/ radio programmes, novels, video games, and toys, as well as parodies and satires. Most iconic of all ‘monster’ portrayals is that by Boris Karloff in the sci-fi film Frankenstein, dir. James Whale (1931), later reprising the role in Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and Son of Frankenstein (1939).

[For continuing debates, see e.g. H.J. Muller, The Children of Frankenstein: A Primer on Modern Technology and Human Values (1970); R.D. Romanyshyn, Victor Frankenstein, the Monster and the Shadows of Technology: The Frankenstein Prophecies (2019).]