Georgian Witnesses

10 / GEORGIAN SITES OF CONTEST FOR VENTING PUBLIC PROTESTS, AT TIMES PEACEFULLY, AT TIMES VIOLENTLY

10.1 OPEN WARFARE

In April 1746, Culloden Moor/Blàr Chùil Lodair, near Inverness IV2 5EU Scotland became the site of the last pitched battle between rival British armies on British soil (though not the last site to witness violent scenes of confrontation and deaths). The battle, fought on 16 April 1746, was over relatively quickly (approx. one hour); and the cause of the Jacobite claimant to the throne,

the ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ of legend, was permanently defeated. However, the battle and the subsequent bloody reprisals left 1,500-2,000 Jacobite combatants either dead or wounded; and a further 500+ taken prisoner, plus others rounded up subsequently. By contrast, the government’s losses were very small. The victorious British general, William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the third and youngest son of King George II, was praised by many supporters of the Hanoverian monarchy and the composer Handel wrote the oratorio Judas Maccabaeus in his honour; but others were repelled by the bloodshed in reprisals after the battle, and critics dubbed the general as ‘Butcher Cumberland’, a nickname that has stuck.

In terms of legacy, the losses at Culloden were long commemorated in Gaelic song and laments, while today ‘Butcher Cumberland’ scores highly in polls of ‘the least popular member of the royal family in history’. The National Trust or Scotland is a sensitive custodian of the battlefield site, taking account both of Jacobite and Hanoverian points of view, providing an interactive exhibition; an immersive film; and battlefield markers, with electronic guide-points available in five languages.

A large cairn (erected 1881) is a memorial to the dead and there are also markers at mass graves of the Highland clans. Continuing archaeological work on the site is revealing new information, and the Trust is also working to restore the Moor to as near to its original condition in 1746 as possible:

www.nts.org.uk/visit/places/culloden

10.2 PEACEFUL INDUSTRIAL CONFLICT IN THE FORM OF A STRIKE

In August 1752 Moushold Heath, a high bluff of heath and woodland, overlooking the City of Norwich, Norfolk NR7 9NT, England, was the scene of a literal withdrawal or strike of industrial labour. A substantial group of several hundred journeymen woolcombers, who undertook the skilled preparation of wool which was used for spinning and weaving to produce high-quality worsted textiles, went on strike to resist a proposed reduction in their rates of pay. They withdrew to a tented encampment at Rackheath on Moushold Heath, funded by their own ‘purse clubs’ (subscriptions), and tested the nerve of the master combers, their employers. The cases of both sides in the dispute were represented in the local press, as they vied for public support. After five weeks, the master combers yielded and agreed to keep the existing piecework rates, whereupon the journeymen paraded back to the city in triumph. It was an example of the industrial muscle of skilled labour, whose specialist skills could not be replaced quickly by strike-breakers. In the long term, however, skilled combing as an industrial process was undertaken by combing machines (patented 1790 but taking time to perfect), against which the traditional handcombers had

no redress.

There is no monument on Moushold Heath to the great strike of 1752, which ended peacefully – and indeed monuments to industrial disputes, which are a common component of negotiation between workers and employers, are generally rare. Moushold Heath itself has been considerably reduced in size by many enclosures from the later eighteenth century onwards, but the remaining Heath is now protected as a Local Nature Reserve and County Wildlife Site. A good impression of the Heath, as the combers would have known it, is conveyed by the painting Moushold Heath (1818 – 20) by Norwich artist John Crome, a weaver’s son.

10.3 A MASS DEMONSTRATION, WHICH ESCALATED INTO THE ERA’S MOST WIDESPREAD AND DESTRUCTIVE DAYS OF RIOTING

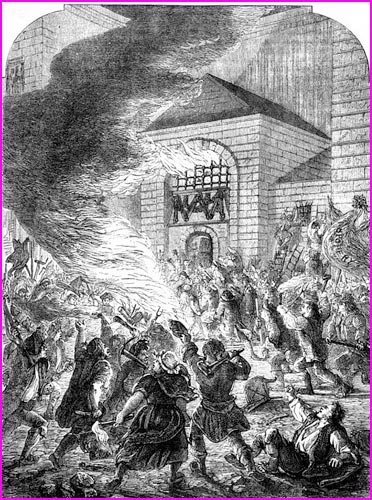

In early June 1780, substantial crowds demonstrated in London, to protest against the 1778 ‘Papists Act’, which slightly ameliorated the legal position of Roman Catholics within Britain. The demonstrations were led by Lord George Gordon, head of the newly-formed Protestant Association, which marched on Parliament to press for repeal of the 1778 legislation. In an atmosphere of tension and excitement, crowds began to attack Catholic chapels in foreign embassies; and, when the authorities hesitated to curb the disorder, destruction and looting escalated. Over a period of several days, there were riotous crowd attacks on private houses of the wealthy, Catholic churches, the home of the Lord Chief Justice, the Bank of England (the attack repelled at the last moment), and numerous London prisons, thereby freeing thousands of prisoners, many of whom were never recaptured.

Determination, ferocity and carnivalesque glee from massed rioters in June 1780, as London’s notorious Newgate Prison burns and prisoners are rescued: as imagined by Victorian artist: Wikimedia Commons

Notably there was no crowd attack upon the Houses of Parliament or upon the royal Court at St James. Nonetheless, the sacking and burning of Newgate Prison, situated in the heart of the City of London, which was the largest and most notorious of all the metropolitan gaols, was an outright challenge to the forces of civil order. The author and Whig politician, Horace Walpole, was no supporter of the rioters but he was interested to observe the full force ‘of a thousand discontents’.

In due course, regiments of the British Army were summoned to restore order, killing several hundred people in the process and wounding others. Extensive damage had been caused both through the loss of life and the destruction of property and through the dent to Britain’s international reputation. Lord George Gordon was put on trial for treason, but acquitted after his defence lawyers showed that he had no treasonous intent. Newgate Prison was rebuilt from the ruins in 1782; from 1783 it became the chief site for public executions in London, (until 1886 when they were moved inside); the prison itself was finally closed in 1902 and the building demolished in 1904.

The legacies of the Gordon Riots were profound but chiefly indirect: respectable opinion was very shocked by the disorder. including among many Protestant Nonconformists who had been among the most active campaigners against any new rights for Catholics. Future public campaigns thus stressed the need for peaceful tactics. In terms of defending the Bank of England, for many years a detachment of the Brigade of Guards was marched there daily, as a sign of government circumspection. In popular legend, there was no great cult of either Lord George Gordon or the Gordon rioters. Their longer-term political aims, if any, were unclear; and the riots’ tactics on the ground too unfocused. The sacking of Newgate Prison did not therefore gain the symbolic revolutionary resonance that was later attached to the Fall of the Bastille in Paris

in July 1789.

The Gordon Riots did not attract any support for a subsequent memorial; but one remnant of the prime target of the rioters’ anger can still be seen behind the Central Criminal Court, known as the Old Bailey: it is the back wall of the old Newgate Prison, visible in Amen Place, City of London EC4M 7BU, England.

10.4 AN ORDERLY ELECTION CONTEST, WHEN RIVAL VIEWS WERE CANVASSED INTENSELY BUT PEACEFULLY – SHOWING A CONSTITUTIONAL TRADITION

IN ACTION

In April/May 1784, the south front of St Paul’s Church, Covent Garden, in the City of Westminster WC2E 9ED, and the piazza in front of the church, together formed the location for the most prolonged and hotly contested popular election of the eighteenth century. The constitution before the 1832 Reform Act had many ‘rotten boroughs’ with tiny electorates, but it also had a number of ‘open’ electorates, which were not controlled by political patrons and which had sizeable male electorates, including not only shopkeepers and tradesmen but also numerous artisans as well as some servants and labourers.

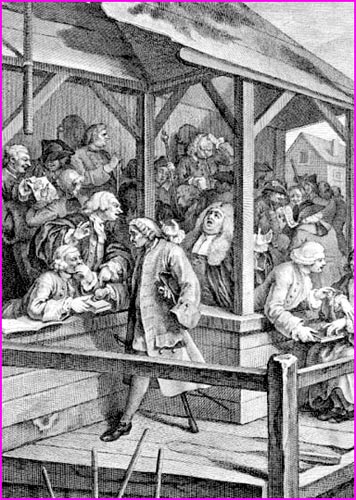

Detail from William Hogarth’s The Polling (1754 – 5), showing open voting in action, as a wounded soldier of modest means approaches the clerk to cast his vote, whilst lawyers argue – as part of a peaceful, if at times rumbustious test of public opinion.

The vote in ‘open’ Westminster, with its proximity to Parliament, was often taken as a proxy for the wider public opinion; so in 1784 William Pitt the Younger, newly in office as Prime Minister, pulled out all the stops to prevent his chief parliamentary critic, the opposition Whig, Charles James Fox, from winning the seat, especially as Fox prided himself as being the ‘Man of the People’. The contest continued (unusually) for 40 days, while electors came to the polling booth, erected before St Paul’s Church, and declared their votes in public, as was then the standard practice.

There were rival slogans, rival campaign songs, rival party colours, rival celebrity canvassers for both sides, and much expenditure on buying drinks or ‘treating’ the electors, although the size of the electorate – then the largest in Britain – meant that it was too large to be bribed en masse to support one side or the other. Finally, Charles James Fox and his electoral partner were declared elected to the two-member constituency, while the Pittite candidate lost, marginally, against Fox. Pitt’s supporters in the constituency then called for a scrutiny, hoping to invalidate the result. But although a few more votes were ruled invalid, the overall result remained unchanged. Charles James Fox gained considerable strength in his opposition to Pitt from the loyalty of his Westminster voters, as he retained the seat throughout successive elections.

The extent of popular participation in the large ‘open’ constituencies, like Norwich, Bristol and Westminster, was important in generating a constitutionalist (though far from fully democratic) tradition in the eighteenth century, when the conventions and rules of voting were being established. Thus each vote was given equal value, whether the elector was a wealthy merchant or a poor weaver; the electoral process was mostly peaceful, though there were some election affrays; and, once the votes were counted, and if necessary re-counted, all sides accepted the result. Thus the electoral battles did not become real battles.

There is no marker at St Paul’s Church (built 1631) to indicate its earlier electoral role; but the covered Covent Garden market in front of it remains a lively urban hub, in the arena where city crowds once massed to witness voting.

10.5 A PEACEFUL MASS PUBLIC DEMONSTRATION, WHICH WAS MISMANAGED BY THE PANICKING AUTHORITIES AND BECAME A BYWORD FOR GOVERNMENT (MILITARY) REPRESSION AND INNOCENT VICTIMHOOD

In August 1819, in St Peter’s Field now named St Peter’s Square, central Manchester M2 5PD, Lancashire, a peaceful crowd of demonstrators, including men and women, gathered in support of a petition to Parliament, calling for votes for all adult males. In response, the authorities panicked, initially sending the local Yeomanry (equivalent of the Home Guard) to arrest the star speaker, ‘Orator’ Henry Hunt (1773 – 1835), and then ordering a British Army cavalry regiment to disperse the crowd. They charged in, sabres drawn. In the confusion that followed, some 7 – 19 people were killed and several hundred injured. The event rapidly became known as the Peterloo Massacre, a name coined by a radical Manchester journalist, making a bitter comparison with the bloodshed at Waterloo. Protest movements in solidarity with the demonstrators were promptly held in many parts of the country. But public responses were divided. Conservative opinion supported Lord Liverpool’s government, which immediately enacted fresh legislation to crack down on large public meetings, to gag radical newspapers, and to curb what the government feared was the danger of popular insurrection. ‘Orator’ Hunt and eight other organisers were tried in March 1820

for sedition.

Although the demonstrators in St Peter’s Fields completely failed in their immediate aims, they had a long-term symbolic impact. They became a rallying-point for liberal and radical opinion, in the long campaigns to obtain the vote for all adult citizens; and the event also in the very long term encouraged the British Army, mindful of the need for public support in a democracy. to be cautious when asked to intervene controversially in domestic politics.

In 1972 a blue commemorative plaque was erected in St Peter’s Square, naming the event but not recognising the violence; and in 2007 it was replaced by a more explicit red plaque. In addition, a new memorial was unveiled in 2019, just before the 200th anniversary of Peterloo: located in front of the Manchester Central Convention Complex, its design (unpopular with some) takes the form of concentric steps, carved with the names of the dead. Peterloo has a long history in popular culture and song, including recently Mike Leigh’s evocative film Peterloo (2018); but nothing matches the power and importance of P.B. Shelley’s poem, The Masque of Anarchy (written 1819 on hearing the news; published posthumously in 1832).

Extract from The Masque of Anarchy

[Note: This poem gained later fame as a manifesto for non-violent civil resistance, showing poetry’s versatility in communicating civic messages as well as intensely personal themes.]

[Addressed to the masses]

Stand ye calm and resolute,

Like a forest close and mute,

With folded arms and looks which are

Weapons of unvanquished war.

And if then the tyrants dare,

Let them ride among you there;

Slash, and stab, and maim and hew;

What they like, that let them do.

With folded arms and steady eyes,

And little fear, and less surprise,

Look upon them as they slay,

Till their rage has died away:

Then they will return with shame,

To the place from which they came,

And the blood thus shed will speak

In hot blushes on their cheek:

Rise, like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number!

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you:

Ye are many—they are few!

10.6 A COMBINATION OF PROTESTS AT HIGH FOOD PRICES, INDUSTRIAL DISPUTES, AND POLITICAL RADICALISM, PRODUCED A WORKING-CLASS UPRISING, WHICH BRIEFLY SEIZED A SIZEABLE INDUSTRIAL TOWN AND RAISED

THE RED FLAG

In May – June 1831, Merthyr Tydfil witnessed a combination of political and economic protests, known as the Merthyr Rising, when the red flag was first flown in Britain as a radical symbol. The immediate confrontation began with industrial protests from local coal miners and ironworkers, incensed by a malign combination of high food prices and wage cuts, but their grievances were also fuelled by political anger at opposition from the House of Lords to the Whigs’ plans for parliamentary reform. In May 1831, working-class protestors in Merthyr and its vicinity repeatedly demonstrated in a state of escalating rebelliousness. In early June, urban protestors, supported by local coalminers, seized control of the town, while a British Army regiment, sent to restore order, was too small in numbers to control the situation. It soon withdrew, after skirmishes causing extensive injuries and some fatalities. For several days, the protestors remained in command, establishing road blocks to halt military reinforcements and ambushing and disarming detachments of local law enforcers.

However, the situation was unstable. Many respectable residents left town in alarm; a mass protest meeting on 6 June dispersed when confronted by armed troops; and the authorities, backed by the army, recovered control on 7 June. Harsh reprisals ensued – but not mass arrests, which would have been too inflammatory. 26 leaders were convicted for their roles in the revolt, several being imprisoned and others sentenced to transportation. One coalminer, Dic Penderyn (also known as Richard Lewis), aged 23, was convicted of stabbing a soldier, and, despite a very large petition for clemency, was hung in Cardiff Market, in August 1831. In 1832 the Reform Act was finally passed, incorporating some modest but not unimportant constitutional changes.

Pressures not only from public demonstrations but also from riots in favour of reform, as in Merthyr and other places like Bristol (in October 1831), helped to force the conservative opponents of reform to give way. Thereafter Merthyr life resumed, complete with continuing industrial disputes, and political support for Chartist campaigning for the universal male franchise, with the formation in 1838 of the Merthyr branch of the Working

Men’s Association.

The Merthyr Rising remains for radicals an ambivalent event. It showed the force of popular protest and the powerful symbolism of the people’s red flag, yet it also demonstrated the difficulties of turning a local revolt into a wider movement, let alone the deep challenge of achieving fundamental changes in the industrial economy and national politics.

Outside Merthyr’s Public Library, High St, Merthyr Tydfil, Wales CF47 8AF, a plaque (unveiled 1977) salutes Penderyn as a ‘Martyr of the Welsh Working Class’; and attempts continue today to obtain for him a retrospective pardon, as the evidence that convicted him was reportedly fabricated and the death penalty seemed disproportionate to the original offence. Penderyn seems to have been the unlucky scapegoat chosen for harsh treatment to discourage the rest.

10.7 A NOTED INDIVIDUAL CAMPAIGNER FOR PERSONAL LIBERTY AGAINST THE POWERS OF CENTRAL GOVERNMENT, IN BOTH ITS EXECUTIVE AND LEGISLATIVE BRANCHES

John Wilkes (1725 – 97), son of a well-to-do London distiller, initially known for his wit and his dissolute lifestyle, developed an instinct for publicizing protest and became associated with five key issues.

FREEDOM OF THE PRESS

The first issue established Wilkes as an active exponent of the power of the press. In 1763 he criticised the government in his opposition paper The North Briton, no 45 for the terms of its peace treaty with France. Crowds in London cheered Wilkes and chalked number 45 on walls and pavements, while the government was incensed – the Prime Minister, the Earl of Bute, being particularly irked by the slight on his Scottish ancestry conveyed by the term ‘North Briton’. The popular outcry was one of many factors which forced Bute’s resignation in late 1783.

OUTLAWING OF GENERAL WARRANTS

The second issue put important constitutional constraints on the powers of the central executive vis-à-vis the individual. In retaliation for Wilkes’s free-booting journalism, the government issued General Warrants for the arrest of Wilkes and his publishers – and the seizure of their private papers. If accepted as valid, such arbitrary measures would give the state unlimited power of search and arrest for unspecified offences. However, in the ensuing legal case, General Warrants were declared illegal and the principle was confirmed by legislation in 1766 – a basic constitutional protection. Having won his case, the irrepressible Wilkes then sued for wrongful arrest – and won damages. Following this precedent, the new American Republic in its 4th constitutional amendment in 1791 similarly outlawed General Warrants, rendering arbitrary search warrants illegal.

RIGHTS OF JOURNALISTS TO PUBLISH PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES VERBATIM

In 1771 a test case involving the Mayor of London, Brass Crosby, challenged Parliament’s right to prohibit the publication of verbatim accounts of its debates. Crosby was briefly sent to the Tower, but public opinion, encouraged by Wilkes, opposed Parliament’s stand. This episode was not the last moment of conflict between Parliament and journalists, but it marked one stage, after which debates were freely published, in the new Parliamentary Register (1775 – 1812) and thereafter (1812 –) in the now standard Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates

RIGHTS OF THE ELECTORATE TO DETERMINE WHO IS QUALIFIED TO BECOME AN MP

The fourth case clarified the rights of the individual vis-à-vis Parliament: Wilkes first became an MP in 1757 but, having been convicted for seditious libel, was thereby technically disqualified as MP. He fled abroad, but returned in 1768 and stood again for Parliament. In a series of elections in the Middlesex constituency, Wilkes topped the poll four times, each time being disallowed after a parliamentary scrutiny. Then, in 1774 he stood again; and, when the electorate remained loyal to him, to cries of ‘Wilkes and Liberty’, Parliament accepted the logic of his victory and he was re-admitted as MP. This test case remains one of only three in Britain to date, which together have established the ultimate right of the electorate to determine who is qualified to stand for Parliament.

(The other two cases were those of Charles Bradlaugh, an atheist who declined to take the Biblical oath of loyalty yet was supported by the electorate in Northampton between 1880 and 1886, when he was eventually admitted; and Tony Benn at a by-election in 1961, when the electorate in Bristol South East successfully supported his right to renounce his hereditary title and to stand for the House of Commons).

and

PARLIAMENTARY REFORM

In 1776, Wilkes was the first person to introduce a bill to reform Parliament, notably by redistributing the parliamentary seats to exclude the ‘rotten’ or pocket boroughs; and to enfranchise the populous cities. It was a significant moment; but Wilkes in this case lost decisively, and the reforms which he advocated were not introduced until 1832. For some years Wilkes remained a popular hero of the radical ‘left’. Nonetheless, Wilkes’s actions at the time of the Gordon Riots in 1780 (see above 10.3) dimmed his radical halo – when Wilkes, then in post as Mayor of London, supported calling out the militia and Army against the rioters. At the general election in 1790, he was doing badly in the polls and withdrew, thereby losing his Middlesex seat, after which he took no further role in front-line politics. John Wilkes remains a radical symbol of successful individual protest against centralized power – and an exemplar of the freedom of the press – even while he was not venerated as a personality and left no Wilkeite party to burnish his legend.

In 1988 a statue to John Wilkes was erected in Fetter Lane, London EC4A 1AY.

THE COURSE AND OUTCOMES OF THESE HIGHLY CONTRASTING CASES SHOWED WHAT INDIVIDUALS AND GROUPS COULD – AND COULD NOT – ACHIEVE BY VARYING FORMS OF CONSTITUTIONAL ACTION AND CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE.