Georgian Witnesses

1/ MEETING THE GEORGIANS USED AS SHORTHAND TERM FOR THE LONG C18, EMBRACING ALL THOSE BORN IN AND / OR MIGRATING TO / FROM

GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND, 1680 – 1840

IMAGES TO PLACE THE GEORGIANS IN HISTORY

1.1 BUILDINGS PROVIDE THROUGH-TIME LINKS

This image of composite housing, underlines the obvious fact that the

eighteenth century fits into a

lengthy history.

1.1 Photograph of Broad Gate, Ludlow, Shropshire SY8 1PQ, England, showing its composite of buildings from many eras: behind is the sandstone archway and rounded turret of the medieval town walls, while the Wheatsheaf pub (front R) dates from the sixteenth century and the gracious town house (front L) is an eighteenth-century wing of the private residence constructed in and around the former town gatehouse in stages between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries.

1.2 ANCIENT TREES DEMONSTRATE AN EVEN GREATER LONGEVITY:

One of Great Britain’s oldest trees (and probably the oldest) is a venerable yew, which is at least 3,000 and possibly 5,000 years old, located in St Cynog’s churchyard, Defynnog, Powys LD3 8SD, Mid-Wales. Another venerable contender is the Fortingall Yew (c.3,000 years old) in Fortingall, Aberfeldy, Perthshire PH15 2LL Scotland. See:

ancient trees inventory in https://ati.woodlandtrust.org.uk

These trees have survived steadily for thousands of years and, more recently, lived through the era of the Stuart kings in the seventeenth century, that of the Hanoverians in the eighteenth century and into the early nineteenth century, the age of Victoria from 1837 to 1901, the twentieth century, including two World Wars, and everything in the twenty-first century to date.

1.2 St Cynog’s Yew Tree (Taxus baccata), which is at least 3,000 years old and possibly 5,000, is located in St Cynog’s graveyard, Defynnog, Powys LD3 8SD, Wales.

Photo: Henk van Boeschoten (2011).

1.3 BIOLOGICAL EVOLUTION TAKES MILLENNIA

All humans world-wide, who lived in the long eighteenth century, shared (with their individual variants) and transmitted to the following generations the human genome or genetic blueprint for humanity. The same applied to the people living in Great Britain and Ireland, and to the further multitudes moving into and out of these islands Here the chosen example of evolutionary power is eighteenth-century Britain’s fastest horse, whose descendants are well documented. Eclipse (1764 – 89) was a mettlesome chestnut stallion, with a white stocking on his right hind leg. He was famed for his speed and his unusual running style, with his nose seeming to sweep the grass. He won all 18 of his prize races by a large margin, and was retired to stud in 1771, when no owner was willing to race his horses against the champion. Eclipse has accordingly contributed to the pedigree of approximately 95% of equine thoroughbreds today – a reminder of the underlying role of biological processes continuing throughout history.

1.3 The champion stallion Eclipse (1764 – 89), painted by George Stubbs (1724 – 1806): the horse’s reputation is commemorated in the UK today in the annual Eclipse Stakes, run at Sandown Park (Surrey) since 1886; and also in the USA by the American Thoroughbred Eclipse Awards.

SYMBOLS OF BRITAIN IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

1.4 THE UNION JACK AROUND THE WORLD

The Union Jack was devised in 1707, at the Union of the Parliaments of England/Wales and Scotland, by uniting England’s red-and-white cross of St George with the blue-and-white Scottish Saltire. Then in 1801, when the Irish Parliament also joined the Union, the flag gained its current design by the further addition of the red-and-white Irish cross of St Patrick. [No change was

made when the Irish Free State left the Union in 1922, as the Six Counties of Northern Ireland did not join the move]. The Union Jack has appeared and still appears in many flags around the world, including briefly in the first Continental Army flag, raised by George Washington in 1776, in what was to become the new United States of America. Most of those usages were specifically linked to Britain’s history as a global colonising power. [See N. Groom, Union Jack: The Story of the British Flag (2005)] But two flags, which today incorporate the Union Jack, commemorate not settlements but historic trading contacts: based upon frequent naval visits from the 1790s onwards, in the case of Hawaii, and significant naval, commercial and mining contacts between 1810 – 40s, in the case of the City of Coquimbo, Chile.

1.4 The Union Jack featuring today in flags/civic emblems of places not formerly subject to British colonial rule: (L) the flag of Hawaii (as adopted 1845) was left unchanged in 1898 when Hawaii became a Territory of the USA and in 1959 when it became a US State. (R) the flag of Coquimbo City, a port in the Coquimbo region in central Chile, has emblems signifying its economic interests, including the Union Jack in recognition of historic contacts.

1.5 TRADITIONAL SYMBOLS FOR THE THREE KINGDOMS

AND, POST 1707, THE EMERGENT BRITANNIA

The traditional symbols for the three kingdoms were retained throughout the eighteenth century, whilst a related set of imagery was also emerging in association with Britannia – symbol of the Union. For the Scottish kingdom, the traditional symbol was the unicorn; the English equivalent was the lion, while, for the Irish, it was the harp.

1.5 Royal insignia of the three traditional kingdoms of England, Ireland and Scotland, visible atop the Irish Customs House (built 1781 – 91), which today houses Republic of Ireland government offices: the striking edifice is located on the banks of the River Liffey on Customs House Quay, between Butt Bridge and Talbot Memorial Bridge, Dublin 1, Ireland.

Post 1707, a parallel concept was emerging, focusing upon Britannia, giving the Scots, English, Welsh and (not without controversy) the Irish a set of plural and overlapping identities. Britannia was usually represented as a proud lady, associated with naval strength and accompanied by a sturdy lion.

1.6 Thomas Bewick’s engraving of Britannia (c.1790). The regal lady sits on a Union Jack shield (pre 1801 design) by the seashore, guarding Britain and its shipping – with one hand she extends an olive branch but remains armed and vigilant, as does the British lion crouching at her feet.

1.7 OVERLAPPING IDENTITIES AND CONTINUING STEREOTYPES:

In practice, there was much migration between the three kingdoms, including much intermarriage. However, stereotypes provide starting points for social engagement – and for standard jokes – even if attitudes are often revised upon further acquaintance. So (in jest) the Englishman was bullish, complacent, and reserved, with a quirky sense of humour; (in jest) the Scot was puritanical and thrifty, with a sardonic wit; (in jest) the Irishman was happy-go-lucky, superstitious and a ready talker; and (in jest) the Welsh were loquacious, fiery, and musical. Recognisable images also recurred partly in reference to cultural tradition and partly to jog efforts at social recognition.

1.8 (L) Toby Jug, a popular utensil in Georgian England, celebrating the hearty, beer-swilling, complacent Englishman; (Centre L) 1792 print showing a proud Scot from one of the British Army’s Highland Regiments, in full tartan regimental dress, complete with rifle; (Centre R) a Victorian print, showing a devil-may-care Irish lad, his hat set at an angle; and (R) a man from Wales, distinguished by the leeks in his hat, not because such sartorial additions were everyday wear but because, in popular tradition, the leek was a symbol of St David, patron saint of Wales, and Welsh leeks were themes of affectionate jesting from Shakespeare onwards.

THREE SURVIVALS, DEMONSTRATING THE IMMEDIACY OF THE PAST

1.9 Here is a tattered but still recognisable lady’s leather shoe, dating from the later seventeenth century: it was found immured in a wall of Ely Cathedral. The custom of hiding shoes in walls or other secret places in buildings was a superstitious practice to bring good luck. In earlier periods, it was possibly done to ward off witchcraft but, by this period, it seems to be a slightly impish assertion of a workman’s presence on the job. Northampton’s Museum of Shoes maintains a Hidden Shoes Index, inviting the public to report any

new discoveries:

https://www.northamptonmuseums.

com/info/20/forms/173/report-

concealed-shoe

1.9 Late seventeenth-century lady’s leather shoe, found hidden in a wall of Ely Cathedral: held by Northampton Museum, 4 – 6 Guildhall Road, Northampton

NN1 1DP, Northants.

https://www.northamptonmuseums.com

1.10 Adventurous eighteenth-century erotica, as portrayed in explicit walltiles at the Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese pub, 145 Fleet Street, London EC4A 2BU: these decorations were probably the accompaniments to a gentlemen’s private club or perhaps a brothel. They include portrayals of vigorous heterosexual sex, flagellation, and lesbian embraces. In the nineteenth-century, the tiles were covered with plaster and forgotten. They were revealed again by a fire in 1962; but, because of their erotic content, were kept locked away. In 2014, they were briefly put on display at the Museum of London and are now being further researched, though as yet the tiles’ future destination remains unclear.

[https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-2550479/Museum-London-

unveils-set-VERY-racy-18th-century-tiles-discovered-fire-Fleet-Street-pub.html]

Among other things, they bear testimony to eighteenth-century interest in women’s same-sex loves, which were known but in general were conducted discreetly.

1.10 One of a set of erotic wall-tiles dating from mid-eighteenth century, originally in an upstairs room at Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese pub, Feet Street, London EC4A 2BU

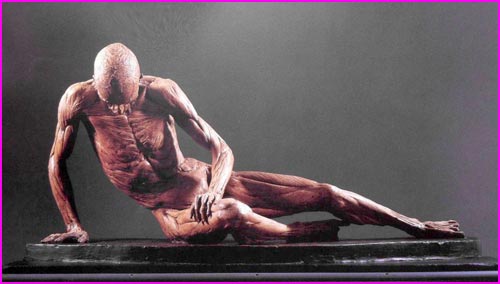

1.11 Here is the flayed body of an eighteenth-century criminal who was sentenced in 1776 to be hung at the Tyburn gallows and then dissected. Initially, a bronze statue of his body – the skin carefully flayed to reveal the underlying musculature – was commissioned as an aid to teaching anatomy. The sculptor was Agostino Carlini (c.1718 – 90), working for the celebrated William Hunter (1715 – 83), first professor of anatomy at London’s Royal Academy of Arts (founded 1768). The original statue has been lost but two plaster-casts, made in 1854, still survive. In order to palliate the grim immediacy of the flayed corpse, the body was posed to imitate the classical Roman marble statue, copied from a Hellenic statue (c.323 – 331 BCE), known as The Dying Gaul. The identity of the eighteenth-century

criminal remains uncertain.

One candidate is a footpad named James Langar, hanged in April 1776. Other possibilities include one of a pair of smugglers, who had murdered a Customs Officer, and were hung in May 1776. Hunter’s students wanted to give the body some individual recognition and dubbed him Smugglerius, which remains his name today.

1.11 Plaster-cast (1854) of flayed body of anonymous criminal, known as Smugglerius, who was hung and dissected in 1776, and displayed for medical students in pose of classical statue, The Dying Gaul: two surviving copies are held at the Royal Academy Schools in London and the Edinburgh College of Art.